'Optimism, Power and Concern in An Age of Apocalypse'

EXCHANGE AND ADAPTATION

In our age of increased technological use, to be Green, we have to make extra efforts not only to save the planet, but also to maintain meaningful connections with people and nature; even with machines. New technologies are increasingly minute, refined, and hard to adapt, yet ever more ubiquitous. Connections with others and our surroundings become superficial as electronic communication replaces the slower, physical processes of old: one of my favourite Noughties expressions is ‘keep it real’, which shows how far we have accepted that we are living artificially and communicating superficially. This instant gratification is proven to rot the brain due to excessive amounts of endorphins, explaining the increase in attention deficiency amongst younger people. People and environments are more quickly changed and questioned today, with our greater access to knowledge. But the more we question the fundamental benefits of our society and environment, the more we undermine deeply held beliefs which underpin our internal life. There are, however, looser, more playful connections available to us, if we can see beyond our 21st century fears and reconnect with some simple joys of life and design.

RISK AND PLAY

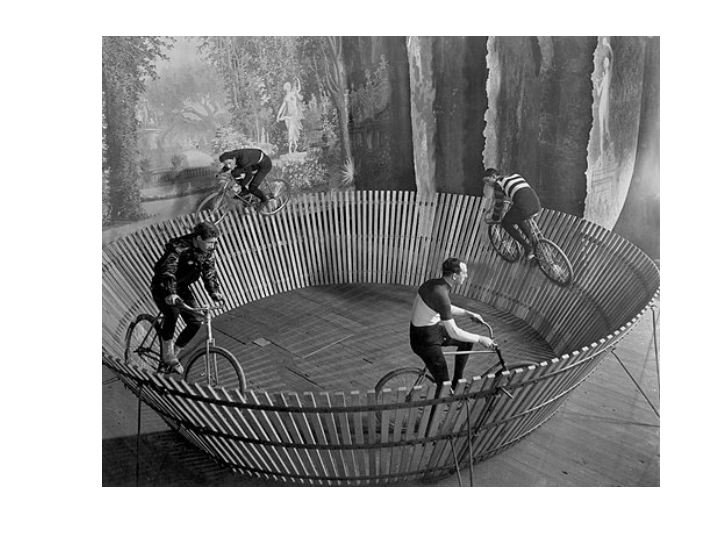

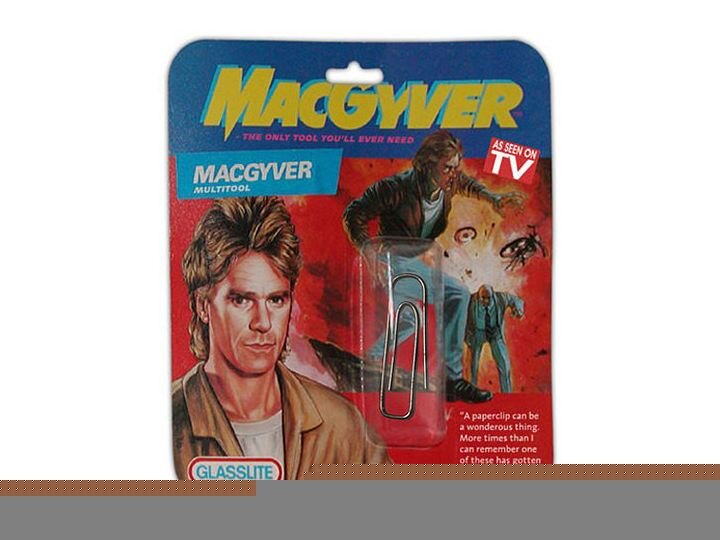

We think we take more risks through games, gadgets, website philosophies and chat rooms: risk our identities through role-playing avatars and adopting the latest opinions. This allows us partially to enact extravagant – I would say, extreme – desires, but are they really risky, let alone fulfilling? Risk-taking is a human condition, part of play and evolution; it is especially important now. Without risk, design in our age of global doom becomes simply a matter of kilojoules and pounds per square metre. The issue of sustainability should not be narrowed to mere energy-saving and function. Delight, vital to architecture and our lives, is so crucial that designers have to risk seriousness for it – not only virtually, but on the ground. More risk-taking, receptivity and delight will bring us back into contact with nature and the here-and-now. From our technological vantage point we can appreciate the natural world with a playful, childlike mind, since we know we have some control over its mechanics. Also vice versa: we can see communications technology as the effective and flashy species it is, but be wary of it, like a big dog. We need architecture that is riskier, and occasionally more challenging.

RECEPTIVITY AND PROCESS

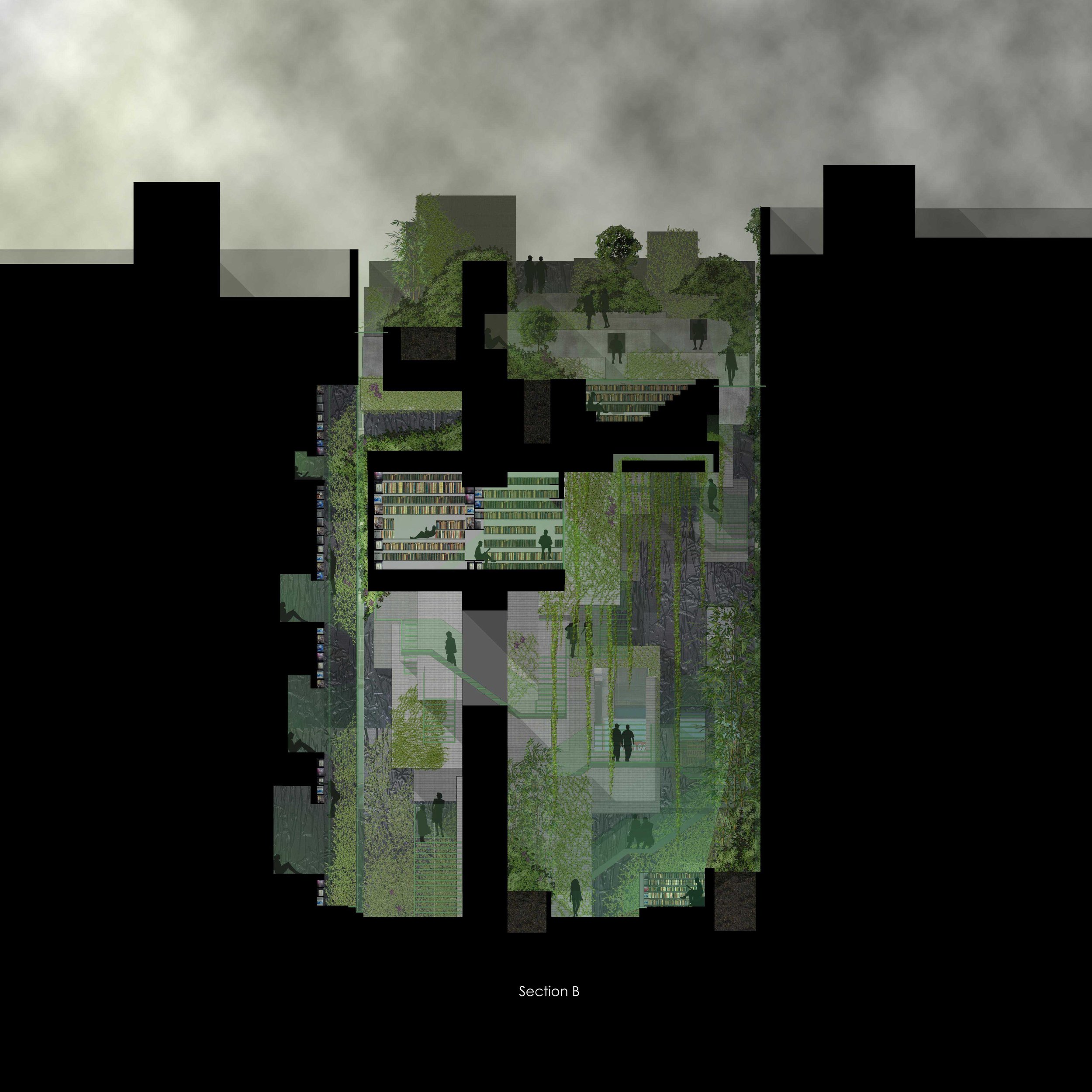

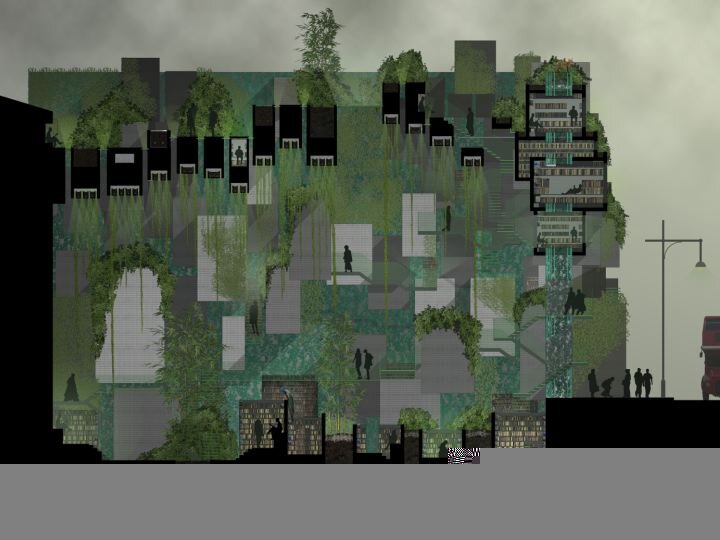

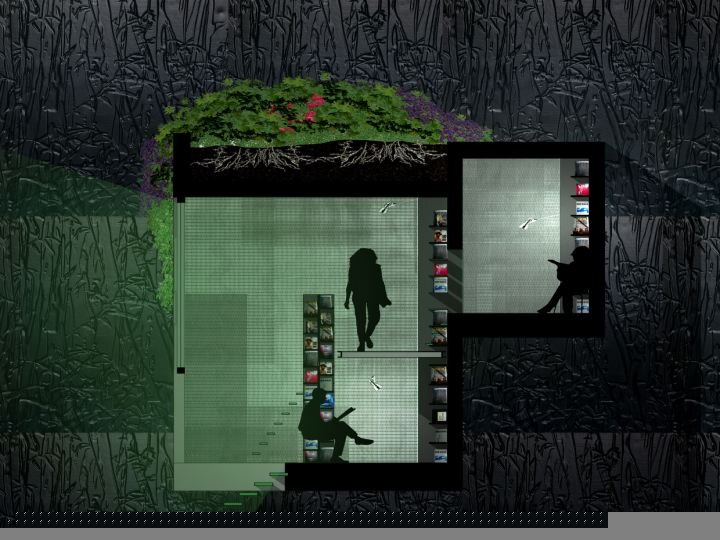

The delights of others and our environment are many when our attitudes to them are receptive. Designers and architects have open ways of working and can often accept a problem positively, as an opportunity for conversion with materials, forms and delightful tweaks into original and appropriate designs. Chance discoveries can be efficient, and often work effectively beyond the initial brief, adding value, as good design should. This requires risk and play, which brings a less academic quality to the process of creativity. If the client, student, builder or our self is not enhanced by our work, it becomes inadequate and soul-destroying. Here function gives way to a livelier design objective and debate; an enjoyable, life-enhancing process and product that should help us design our way out of global predicaments. Our approach to and recognition of life is the issue, not simply saving it out of duty. We need architecture with more gaps that allow unforeseen life to grow.

DELIGHT AND VALUE

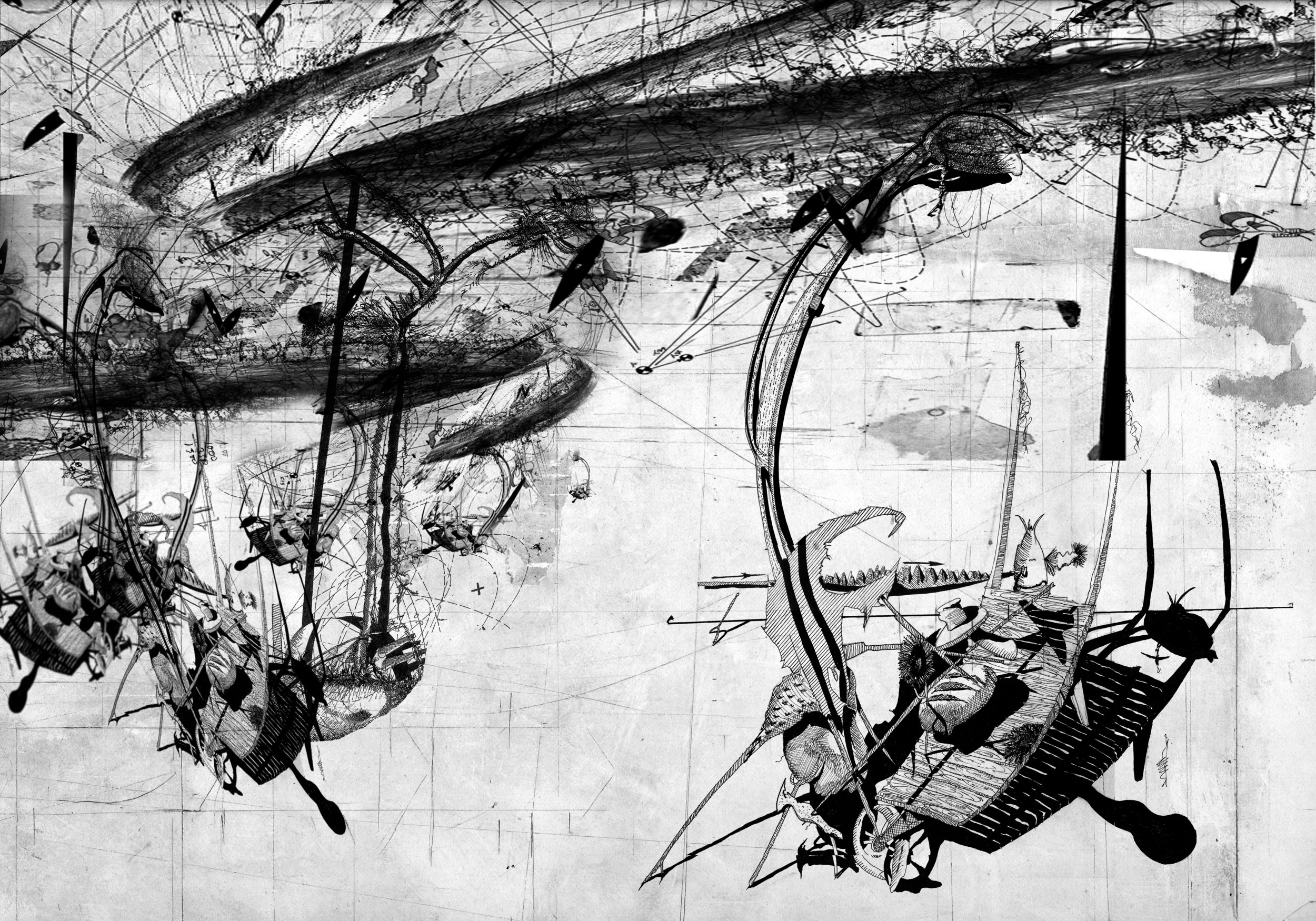

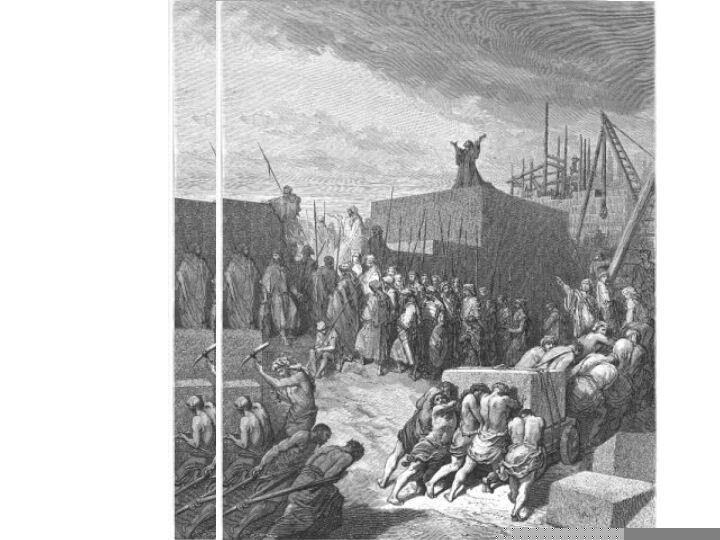

Going with the flow is Zen-like: it allows the hand, as much as the brain and eye, to do the thinking. Gestalt, holism, happenstance – whatever you call it, the main driver of the process is delight. Delight is the driver, product and prism through which it can happen. I use the word ‘value’ carefully, as many question its economic attributes and cynical application, but what would happen if delight were the currency of architecture, including the product, its functions and efficiency? The test of a building would lie in its experience: the building of it, running a contract and inhabiting the space would then all be connected. The Bible talks of building the Temple silently, which sounds ridiculous, since a building site is often more like a war zone, but suggests a benign and appreciative modus operandi for each participant involved. We need architecture that is seen as a continuum.

INDIVIDUALLY GREEN

Alongside environmental proposals for green architecture, we need to reappraise how each of us individually appreciates and enjoys our surroundings, ourselves and others. If we are saving the life of the Earth, let’s make or have more of it! This is not for governments or scientists to dictate, but requires single-mindedness from individuals. We need to look at the way we live; to have more confidence in designing our lives and relationships with nature and others, and be guided from within. This is a battle not for votes, but for hearts and minds, which cannot be won by information alone. Individuals, not governments, change hearts and minds. We need architecture where strangers can meet and talk together more freely.

INDEPENDENT ACTION

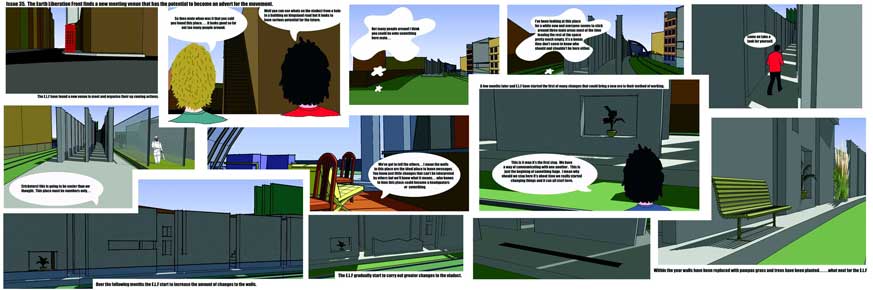

We need to evolve a new model of ‘engaged citizenship’, in which we realise that the way we live affects everyone around us, and develop new ways to take up our responsibility – which I believe means the ability to respond appropriately. We need to take ‘participatory democracy’ to a new level, where we take responsibility for creating culture, including the environment. In return, we’ll get the feeling of a life fully lived, in which we are not victims of the system. We can see guerrilla gardeners and self-builders making the first moves at this: another example is individuals creating and publishing film, music and text on Facebook, no longer simply buying what is marketed at them, but creating their own products through playful design. This open-ended creative process, peculiar to our relatively privileged times, may ultimately lead to the environment, as building suppliers respond to this market, and marketers recognise a new type of consumer. We need an architecture of new client-based building systems, which offers the individual customer the chance to be producer.

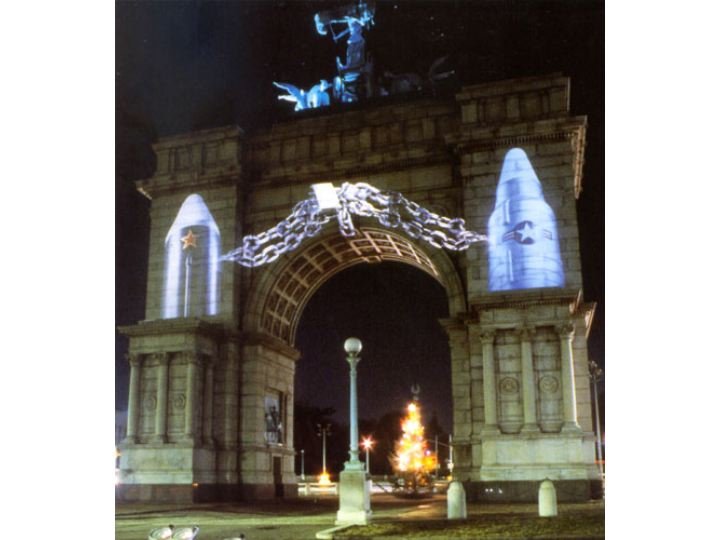

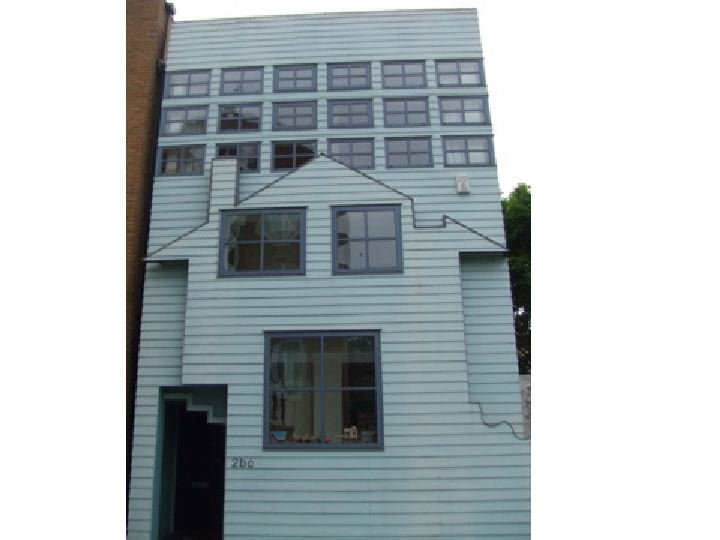

POLITICS AND LOOSENESS

Buildings once publicly expressed an institution’s or a patron’s power. But how will the consumer and independent producer choose to express themselves once the above building systems are available? Budget, site and fashion may form this architecture of diversity – or will it become yet another brand of Lego? Buckminster Fuller foresaw that factories and individuals would become symbiotically connected to make production and consumption most efficient; Gibson and Ballard presented a more dystopian view of ghetto enclaves for corporate and specialised groups. In both scenarios the natural world is irrelevant; all is functional, including the ecological groups. Hundertwasser became aware of a green energy mob mentality when he described ecology as becoming an issue of simple science, which to such an artist seemed anathema, but we now find acceptable. Somehow you can greet someone more generously when walking along a stream than in a conference hall. We need architecture that allows integrated groups to meet in hallways with fish-filled streams.

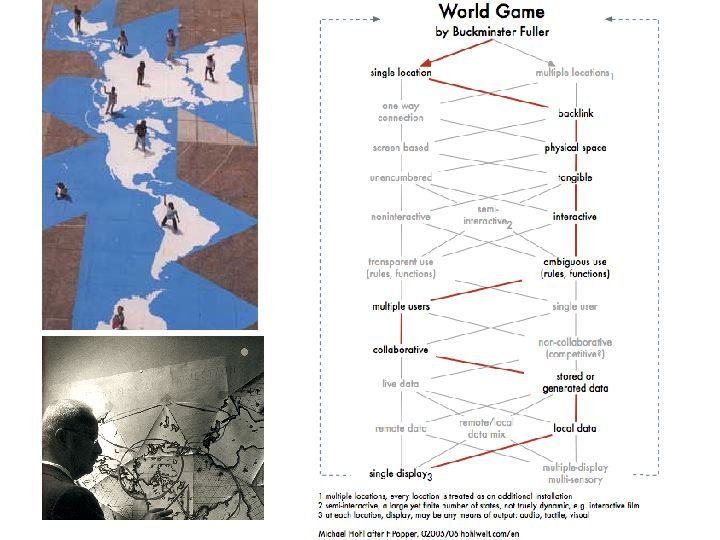

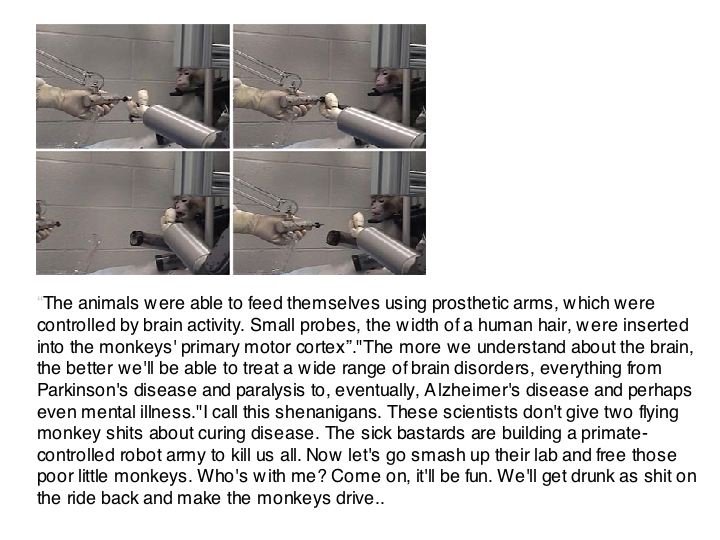

CYBERNETICS AND BLISSFUL IGNORANCE

Like most super-new technologies, the Internet and cybernetics stem from military inventions. This is fine with Velcro, but how do we interact with and appreciate the net, biotechnology and electromagnetic waves if we cannot see them, let alone adapt them? Perhaps we don’t bother; perhaps we can once again be in the Garden of Eden – as long as we ignore what’s going on. The only people who can really engage with the new technologies like electromagnetics, genetics and boson quarks to influence our global existence are a small elite of specialists. Maybe it’s a good thing we are left behind to frolic in the leaves,.as long as they keep the world going. But remember that cybernetics was invented by Norbert Weiner for military purposes, to control the minds of people and animals. This science can now function through the application of electromagnetic waves and monitored communications devices. Thus the prosthetics we see today used for basic physical function may soon become tools of some other function, especially if we can be rewarded for using such technologies. The play, risk and appreciation may be experienced by the participant or society consciously, but implemented for purposes they know nothing of; we may soon be able to get on with our own leisure and prosthetic expressions whilst unknowingly performing tasks useful to larger, unseen systems. As long as we can ignore the elephant in the room, we need a functional leisure architecture that benefits us whilst also offering some input from wider unseen applications.

TECHNOLOGY AND THE INVISIBLE AGENT

In a media-driven culture, expression and oppression can be closely linked, no longer through propaganda but by hype and promotion. Therefore we need to be well centred to know what we really want to express or take on board. The desire to extend our faculties has become an addiction of the most material kind, and we are less selective of the data or gadgets we invest in. Expressing ourselves indirectly via technology is replacing deeper, direct human connections, and this ultimately controls the quality of our relationships. But something is occurring here beyond our control; technology is evolving like a species itself. Look at the mobile phone or satellite, the camera or observatory: all these are now used to observe the Earth and ourselves – maybe even themselves. Could Gaia be constructing a new self-reflexive mechanical species for the benefit of the planet? Is there a mechanical Darwinism afoot? Perhaps I’m paranoid to think that we are becoming the environment, both physical and cultural, for technology. It inhabits our world and we its. The Earth, God, group-consciousness or whatever, is driving humankind into a new space, and I, like Noah, want to take some good old-fashioned nature with me, and some friends and a few physical machines. IT has been emerging and expressing itself through man as maker for centuries. Today, however, when all the disparate components and tools become interactive and interdependent, even intergalactic, we find ourselves surrounded not only by hardware, but by an ecology of our desires. These manifested desires may encourage us to act in new ways that question the ethics we have taken for granted and depended on for social benefits for so long. We need an architecture that expresses and encourages moral imperatives and individual manifestations. while reminding us of past constructions and elemental life.

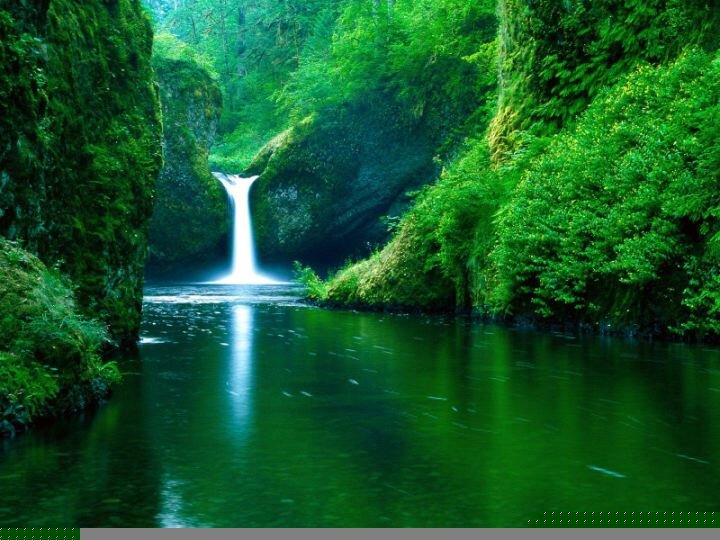

LIFE: LIVING AND SAVING

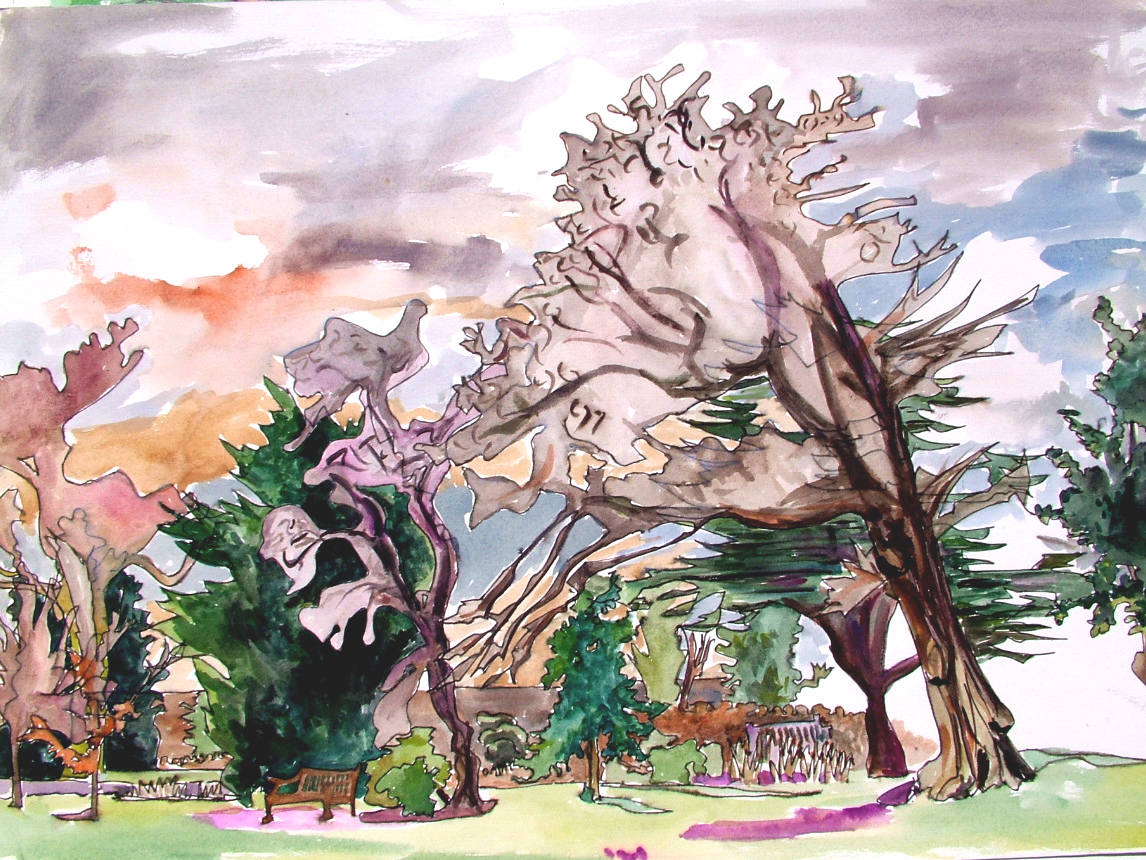

We are very inclined to imitate, to copy ideas, and what happens? The flame of creativity is lost and only the symbol, the picture, the word remains, without anything behind it. It is understanding that is important and creative, not just information stored in memory or given to us via the internet. We need to be able to comprehend immediately, in the moment. Most of us, particularly academics, are so burdened with information and the intellectual authority of others that our intuitions and lives suffer as we try to get on in the world. Information makes inner life very complex, as combative ideas increase while more abstract ones want resolution and harmony. So to connect with life’s river and see the natural world’s beauty we have to rise above the problems of environment, the shaping and fears of society, stop imitating others: to find our own way. Life is always volatile, never still. Yet today’s excessive functionality and information prevents us from having particular types of contact with life. A new world cannot be new if we have an idea about it; it will be born of what we have read of other people’s ideas. Life will guide me appropriately if I am free to feel what I want loosely. If I see a beautiful tree I may write a poem, make a painting or even a building describing not the tree, but what it has awakened in me. The awakening is connected to the tree that sparks my feeling, which is intuitive, not mechanical; it is in fact some sort of exchange between our internal workings and the world. If we can remain centred this allows all our mental workings to be balanced and we will thrive in life, not just survive the day. Overcoming fear requires the optimism of a snowdrop struggling to grow in Spring snows. We need an architecture that offers small but life-enhancing spaces for us to enact life’s rituals with ease and freedom from fear.

POLITICS OF OPTIMISM CONCLUSION

Cynicism stops joyful responses to life’s opportunities, and is the attitude most likely to conform to the desires of the powerful whose wealth is tied to planetary destruction. Fear and cynicism are encouraged by the grim coverage in the news. We are suffering from ‘solastalgia’ about the loss of the natural world and compassion for the suffering of millions. Yet we should not give in to the narrative lure of collapse. The cynical dynamic we see in media and political debate today stems from incorrect assumptions, including:

We are incapable of solving the earth’s problems.

Bold solutions are ‘unrealistic’ because they involve unbearable costs.

‘Realism’ really means ‘in the best interest of those doing well today’..

Small steps and half measures are the appropriate course of action.

Combined with the politics of fear, this is best thought of as a cynical ‘politics of impossibility’. Where no one believes things can change for a better future, despair is logical, nobody changes anything, and those benefiting from continuation of the problem are safe. If we want a better environment for ourselves, the Earth and our designs, we need to challenge cynicism. If we all introduced intelligent reasons for actions to show that a better future is possible, we could start to act out our principles. Consider, therefore, a politics of optimism, where the assumptions are:

Realism is defined as ‘within our capacity’ and ‘necessary’..

We can create environments that solve the world’s problems.

Improving the prospects of most people and their environments and the Earth incurs costs. But the returns are attractive: eco-stability, economic prosperity, international security and human well-being for now and the future.

We publicly commit to appropriate actions and start defining win scenarios we want to create.

This optimism needn’t be naïve. We know people are fallible and self-interested. We can stress the importance of informed decision-making, demand rigour and note uncertainty. We can anticipate future setbacks and even total failures more easily if we acknowledge the struggle with optimism. If we do so, we shall liberate ourselves from the burden of despair this millennium has been given. And to do so, we as architects have to question some basics of how we relate to the design processes, nature and technologies that form the environment today; and not be ‘green’ with fear.