'The QuietUde of Normality'

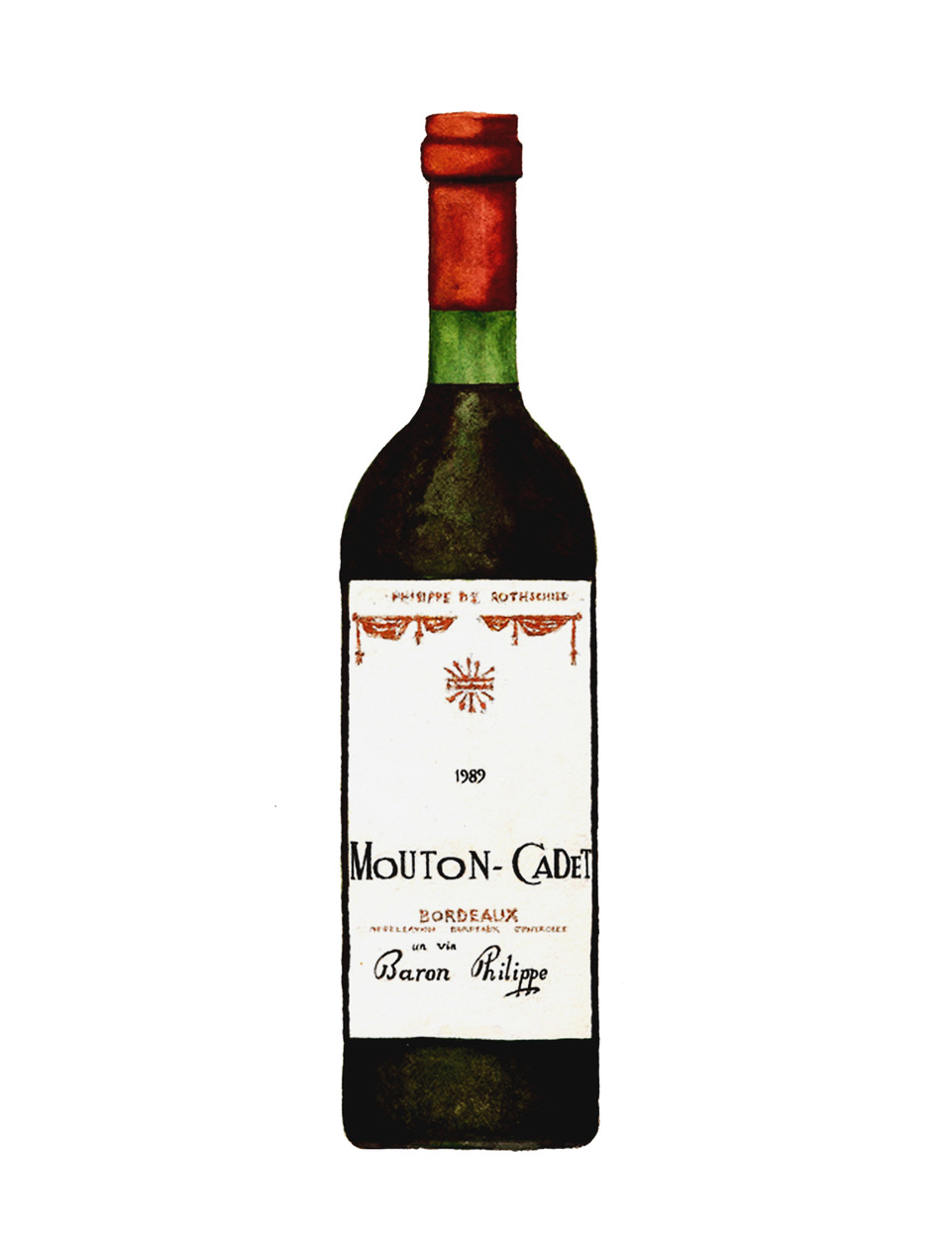

I enjoy traditional timeless art and architecture that does not shout, express, or mean anything. These things are like silent influences that form who we are without us realising. Many artefacts, products and objects that have become simple commodities of our lives and are no longer questioned are formative props or vessels of our lives that go unnoticed.

There is the countryside of quiet churches, silent hills, empty coastlines and meaningless forests. They hint at an art or space that is quietly accommodating and yet has a distinct personality, a self-‐evident character that is normal yet uncharted.

Could there be an art or architecture of less, or the everyday, that doesn’t "say" anything, but in the words of Elia Zhenghelis is a "dumb" thing that we can inhabit and perform with as we choose, that in its accommodating quiet way allows us to engage with it freely?

The everyday and mundane objects of life allow the happy person to play freely because they are without obvious cultural, intellectual or programmatic constraints.

The simple and prosaic artworks and spaces are generally speaking authentic yet neutral; with no obvious signs ‐ at least to the modern or urban man. Perhaps they offer us a way to re ‐see or re‐engage in normal, unprogrammed art and space in an unquestioning way; an open, innocent or even naive way.

Many architects and artists are now searching for something more engaging than the contemporary avant‐garde. So getting back to our roots, to the traditional, and enjoying being engaged in a less critical, more basic way offers new/old pleasures. It gives us an opportunity to discuss "normal" or "simple" or even "modern folk".

One way to develop an accessible, silent space of art or building is through the use of myth or folklore, which is universal and engages at a subliminal level, its power grounded in bottom‐up local experience and everyday mythic oppositions.

Architectural and artistic visions often portray to us the exceptional ‐ many architectural or art students and theorists seem to wish to deny the joys of reality, and see the avant ‐ garde as a way to escape normality, rather than trying to generate original impulses that grow in an organic way from the grist of the everyday experience.

I enjoy more reality based challenges, and prefer to design for the average person with minimal theoretical intrusion. Reality and normality are today new realms of delight and transcendence, from which we can generate spaces and visions that may be applied to modern life in more engaging ways than the ecstatic screaming we see all around us so often.

In our communications dominated times of increased messages we are bombarded with meanings via multiple media, advertising, symbols, public events, music lyrics, bad conversation etc. But there seems to be less sense permeating through. This glut of cynical meaning has become meaningless, as contemporary philosophers recognize. It seems we have lost "ground level" and are looking to keep it "real".

We have gone beyond Maslow’s cited necessities of food, shelter, clothes and warmth, and now, even with our cars, flat screen TVs and cell phones, and in times of relative peace and security, we are still needy for meaning and value in our lives.

It may be that the very meaningless of modern life is in fact making us tire of looking for meaning, and we may be beginning to settle upon finding simpler existing normalities and enjoy the soothing timeless joys. These offer subtleties that are more ephemeral, less conceptual, quieter and more recessive. It may be that here in this quietude we can be still, and once again experience ourselves without striving to figure out all the answers.

A prayer, or Zen‐like experience can be enhanced via the arts or an environment of less, cut back to an almost monastic essence that can offer mindfulness. But could this new level of minimalism be achieved by accepting that the minimalist is in fact no such thing? Minimalism is in fact a huge effort of cultural contortion and theatrics, loaded with meaning. It shouts. Less is often too much. In too much less there is in fact a vast amount happening within the void.

What, therefore, could an art or architecture that has subliminal meaning, unseen influence, that was simple yet authentic, allow us to be or do? Could it function psychologically as a space that both engaged the viewer or inhabitants, and left them to be free to be themselves ‐ on their own terms with their own imaginations?

Is it possible that we, the inhabitant and viewer, actually ‘create’ spaces ourselves when we are in them or looking at them? Could a space’s more silent existence make it disappear, and therefore allow us to extend ourselves into it, and engage more fully with the experience of being in space by not caring what it means ‐ by being mentally quiet and drawn within an artwork or space? I wonder if there could be an architecture or art of meaninglessness, that doesn’t ‘say’ anything ‐ that simply allows us to act freely, as naive youth once did.

The forest and much of the countryside is generally speaking neutral, free of cultural or programmatic constraints. It has no obvious signs ‐ at least not to the modern or urban man. Perhaps this is why it frightens some people. Its very normality offers a sort of void to our meddlesome minds.

Some people in conversation will stay quiet and listen, and this allows you to engage easily with them. They ‐ however dumb or quiet ‐ seem to offer you the chance to exist through some notion of consensual shared experience of quietness for the moment. I wonder could this communing happen with architecture, planning and painting.

What we need these days is an appreciation of normality -‐ which does not try to express, or mean, anything. Could there be an art that is meaninglessly quiet, simple, accommodating, and yet normal too? Could normality offer us a way to lose another layer of meaning and help us to find quietude?

Now we are starting to study the cosmos ‘outside’ with quantum mechanical tools, let’s not forget that there is and has always been a motive force which dwells within us. With our feet of clay we stand on and in the Earth. We are vessels containing, for some, simply blood, guts and thoughts, for others the Holy Spirit and a motivating force. Bricks contain our objects and furniture, clothes our bodies, glass and clay our liquids, metals and steel our heavier materials, mechanisms, paper and switches our thoughts and actions. In short, we vessels are surrounded by other vessels of containment, and together we recreate more containment in turn for a motive force which stimulates and animates the seemingly dead matter of earth.

We humans who make and recirculate, transmute and animate Earth’s matter allow a relocation, distribution and sharing of clay via the motive life force. Perhaps only when we have achieved the simplicity to understand that we have feet of clay can we realign ourselves with the materials of the Earth and this motive spirit, which drives us to work on it in its base simplicity.

A motive spirit has always surrounded us. When you next see an object, tool or artefact, consider that someone made this with a motivation not simply of greed and need, but a humbler, basic, and more powerful force that has inspired inventors and makers since the cave dweller. The steam engine, the rocket, the printing press, the television and the computer were invented by people of faith. Even Darwin was a committed Christian, who saw the motive force working on the recontainment of ourselves and this spirit within more evolved bodies.